Our first deep-dive into Strategy Safari takes us to the land of prescriptive strategy making.

This is what numerous consulting companies and strategy thinkers told top managers they should do if they wanted to have a good strategy.

Chances are this is what you thought strategy making was about too. After all, strategy is a very good plan, right?

Well, as I mentioned in my previous article: prepare to be surprised.

The Design School: “Give me a business case”

This school of strategic thought can be traced as far back as the mid-1950s. Before you think that this is outdated, let me tell you that this is the school that gave us SWOT analysis and largely influenced strategic management as we know (and cherish) it nowadays.

The design school proposes a model of strategy making that seeks to attain a match, or fit, between internal capabilities and external possibilities.”

In other words, as a strategist, you need to analyze your environment pointing out opportunities and threats it presents, then take into account the strengths and weaknesses of your own organization. Once done, you must find a way to overcome or mitigate your weaknesses and use your strengths to avoid or reduce threats and seize the opportunities.

And this is how the strategy is made.

There are a few caveats here, and the first one is that to be a strategist, according to this school of thought, you must be a CEO.

That’s right, there can only be one strategist – the Chief Executive Officer – the “architect of organizational purpose”.

Precisely because it’s one mind that designs a strategy, the process of strategy formation should be kept as simple as possible and the strategy itself should be made explicit and simple as well (otherwise how would a CEO explain it to the entire organization?).

Finally, strategy should be unique. It should be tailored to the individual case and deliberately build a “distinctive competence”.

Only after these unique, full-blown, explicit, and simple strategies are fully formulated can they then be implemented.”

Thus, thinking (strategy making) should be separated from acting (strategy implementation).

After all, with a big picture in mind, your CEO knows better.

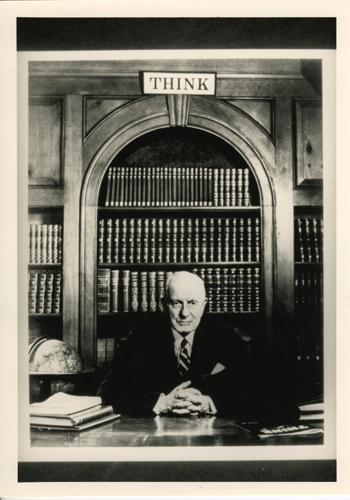

The picture below was suggested by the authors of Strategy Safari as the one image “to capture the sense of this school”.

This picture was distributed to thousands of the IBM employees in the late 1940’s.

As simple, logical, and self-explanatory as they may seem, the ideas of the design school bend quite a lot, once you give them a reality check.

First of all, “how does an organization know its strengths and weaknesses”?

Is it even possible to tell what are those if you don’t test them in action?

Strategy Safari argues that they might be dependent on context, time, and application. Conducting a SWOT analysis once and expecting it to magically produce a perfect unique strategy within the brain of a single executive sounds like a beautiful business case study but real organizations need more than that.

Secondly, “the CEO knows it better” works for certain situations such as a startup or failing organization requiring a revamp but it is quite audacious, to say the least, to reduce all organizational actors to the CEO will-bearers and external actors to “faceless environment” that the CEO should navigate through instead of interacting with.

Finally, matching the external situation to the internal state sounds like a good idea for a stable, predictable environment. Once you add ambiguity and a high level of uncertainty into the mix, the question arises, how many SWOT analysis do you need to conduct, and how often?

Even more importantly – how fast do you need to implement your unique simple strategy before conditions change and it is no longer viable?

If the design school model has encouraged leaders to oversimplify strategy, if it has given them the impression that “you give me a synopsis and I’ll give you strategy,” if it has denied strategy formation as a long, subtle, and difficult process of learning, if it has encouraged managers to detach thinking from acting, remaining in their headquarters instead of getting into factories and meeting customers where the real information may have to be dug out, then it may be a root cause of some of the serious problems faced by so many of today’s organizations.”

All in all, the design school ideas can be found at the foundation of most practices of strategic management today, whether we are aware of it or not. But they need to be applied with caution and paired with the ideas of other schools (as we can see in future articles).

The Planning School: “I’ll give you a plan”

The 1970s saw a rise in formal strategic planning that saw strategy formation as a big planning process.

There are hundreds of … strategic planning models. […] Most reduce to the same basic ideas: take the SWOT model, divide it into neatly delineated steps … give special attention to the setting of objectives on the front end and the elaboration of budgets and operating plans on the back end.”

Simply put, based on a forecast that predicts the environment, top management should roll out strategic goals (aka “strategic plan”) that are further broken down into functional goals that, in turn, are broken down into departmental goals, and so on down the line till they reach the front-line teams and individuals who receive their very specific objectives. Once all objectives are completed by everyone, the strategic plan is complete as well.

And this is how you create a strategy and make it happen.

Unlike the design school which saw the strategy making process as creative and informal, the planning school highly formalized it. Now you had all sorts of plans in place and the more complex and detailed they were, the better your organization was set to succeed [allegedly].

Also, instead of a single mind of the CEO, the planning school handled the strategy formation to a group of planners. The CEO was still the architect of strategy but instead of designing strategic plans, he or she would merely approve them. (The 1972 publication, quoted in Strategy Safari, suggested that planners should “involve top management at key points, only at key points,” such as four days per year in one steel company.”)

As you can imagine, the authors of the book give quite a lot of critique to this school of thought.

We wish to make clear that our critique is not of planning but of strategic planning – the idea that strategy can be developed in a structured, formalized process. (Planning itself has other useful functions in organizations.)”

Major critique points include the fallacy of predetermination (planning assumes that your environment is stable enough to be controlled – but is it truly?), the fallacy of detachment (instead of locking themselves up in the corner offices, effective strategists should immerse themselves in the daily details and “abstract strategic messages from them”), and the fallacy of formalization (analysis is great but strategy is about synthesis. Can you truly create a strategy out of analysis?).

Overall, Strategy Safari claims that strategic planning has never been about strategy making. It does not describe nor reflect how strategy is actually made in the organization.

Analysis and forecast promoted by this school should feed into strategy and the planning of efforts should follow once the strategy is created. But analysis and planning cannot substitute the strategy making itself.

Otherwise, we will end up in a situation where we extrapolate our past activities into the future and call it an effective strategy making.

to THINK again…

The Positioning School: “Want some generic strategy?”

If you thought the 1950s and 1970s were far away, the final school of strategic “prescription” actually takes its roots in 400 B.C!

The very late Sun Tzu is to this day mercilessly quoted by various strategy “experts” most likely because it is prestigious to compare the marketing efforts of a small B2B company to the clever battlefield techniques applied by the ancient Chinese generals.

However, as we will see further, leading an ancient army into a battle and positioning a business on the market is not quite the same, even when applied broadly.

The positioning school truly starts in the 1980s with Michael Porter and his famous book Competitive Strategy. While the two schools we reviewed above claimed that the number of possible strategies was infinite, the positioning disagreed.

The positioning school… argued that only a few key strategies – as positions in the economic marketplace – are desirable in any given industry: ones that can be defended against existing and future competitors.”

Basically, unlike the design school which said that the CEO should come up with a unique strategy matching the external conditions to the internal state of the company, the positioning school claimed that there is a known set number of strategies that do that matching perfectly. These strategies were called generic. They were presented as identifiable positions on the market (thus the name of the school) and dominated the business world for a couple of decades.

And just like the planning school, the positioning school promoted the role of planners (versus a one-person CEO) with a major difference: these planners now became analysts (and were often hired externally as consultants).

With the positioning thought taking charge, market share became the major focal point of any decent strategist, and being the market leader became an obsession (at least in the United States).

For Porter, specifically, 3 generic strategies would allow a business to achieve above-average performance in the industry:

- Cost Leadership – a company must be a low-cost producer.

- Differentiation – a company must develop a unique product or service to achieve brand/customer loyalty.

- Focus – a company must concentrate its efforts on a narrow market segment (particular customer group, product line, or geography).

Pick and choose, as they say.

Of course, it doesn’t mean that the matter is this simple. First, you need to analyze your market and your organization and this is exactly why diligent analysis is the cornerstone of the positioning school.

Like the other prescriptive schools, the approach of the positioning school has not been wrong so much as narrow.”

The authors of Strategy Safari criticize Porter and his followers for the narrow focus on quantifiable economics (versus social, political, and other data), their bias toward traditional big business and stable environment, and their emphasis on analysis and calculation versus learning and getting their feet wet in the frontlines.

Per Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, and Lampel, the positioning school is the most deterministic of the three schools.

While proclaiming managerial choice, it delineates boxes into which organizations should fit if they are to survive.”

In a way, this creates a “toddler choice” for the senior leaders: do you want your competitive advantage in a blue cup or a yellow cup of “generic strategy”?

With its emphasis on analysis and calculation, the positioning school has reduced its role from the formulation of strategy to the conducting of strategic analyses in support of that process (as it proceeds in other ways). […] Thus, the role of positioning is to support that process, not to be it.”

Failed prescriptions and why does it matter?

So in summary:

The design school told us that to have a strategy you need to conduct a SWOT analysis (or something of that nature) and send it to your CEO – he or she in their eternal wisdom will come up with a simple unique strategy that they will further cascade down to the organization to implement.

The planning school said that you need to have a group of skilled planners who will perform a forecast of future conditions and come up with a strategic plan for the organization. This plan will encompass all the goals for every division, department, and team so that the organization can successfully move in the chosen direction.

The positioning school claimed that there is no such thing as a unique strategy and also your planners should actually be analysts (and preferably paid consultants). These analysts will conduct a thorough analysis of your marketplace to determine which generic strategy you should apply for your organization – a recipe for success if you will.

Each of the schools made an assertive attempt to tell us how the strategies should be made. Whether it’s a unique strategy, a generic one, or a complex strategic plan – each of them emphasized the importance of a thorough analysis of the external environment and the necessity of strategy. They separated strategy making from implementation and introduced a large number of techniques and vocabulary that are used to this day.

Whether we are aware of it or not, we are using quite a lot of their heritage in today’s strategy making.

But we need to do so with caution.

with Thomas J. Watson Sr.

The problem is truly in the nuance.

When we say that some pieces and parts of each school’s thinking make sense and is still applied to this day, we should remember that when those schools were prevalent in strategic management, those pieces and parts were the only ones available and deemed essential.

For instance, most companies establish yearly goals and have strategic planning sessions but they correct themselves and update their plans when circumstances change. Surprisingly enough, this was not the case in the past. Planners could not be wrong – it was always the implementers’ fault. This is why the planning school is no longer dominating the strategic management space. And this is why we should remember to adjust our plans as necessary.

As for the positioning school and its fall from grace, Strategy Safari cites a great example of Honda entering the US bikes market in the 1960s and completely overthrowing British bike import by the late 1970s. While British companies were preoccupied with their US market share and cost, Honda created their own niche and dominated the market. All this – by immersing its managers into the frontlines instead of trying to lock them up in the ivory tower in Tokyo or pay a consulting company to analyze the US market (market analysis would have not demonstrated a niche that had not existed yet).

So, coming back to the headline question: would you accept a prescription of generic strategy?

And the answer to that is you shouldn’t.

Unlike generic drugs, generic strategies didn’t prove to work as well as unique “brand” strategies and so in nowadays world you should probably avoid them altogether. Unless, of course, your environment is well established and stable so you can get the hard data reliable enough to be analyzed and inform your generic strategy.

Needless to say, this isn’t the case for most businesses.

Lastly, none of these three schools truly described the strategy making process itself.

The design school assumed that a strategy would magically appear in the CEO’s mind, and the planning and positioning schools equated their analytical efforts that should feed into a strategy to the strategy itself.

Luckily, we have 7 more schools of strategic thought that will help us to understand how truly the strategy is made.

Next week, we will take a look into the mind of a strategist and explore strategy making as visionary and mental processes. Stay tuned to learn more!

Discover more from Knowledge In Action

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] the previous deep-dive article, we explored the prescriptive schools of strategy making (aka this-is-how-you-should-do-it […]

LikeLike

[…] Would You Accept A Prescription Of Generic Strategy? […]

LikeLike